Original Author: Deborah Hardoon, Poverty & Inequality Lead | Development Initiatives

The Leave No One Behind commitment puts the most marginalised and vulnerable people at the centre of efforts to reduce poverty and inequality around the world. This requires the identification and targeting of the furthest behind as well as empowering individuals and groups to challenge the structural drivers of exclusion that they face, including in the process of generating data and evidence.

Intersectional analysis of multidimensional poverty data to identify who is furthest behind

Data that measures multiple dimensions of poverty and includes variables that can enable a disaggregated analysis, by things like gender, geography and their intersection, can tell us who is furthest behind and on what dimensions of poverty. Quantitative data collected through censuses, nationally-representative household surveys such as the DHS or MICs programmes, or by international agencies seeking comparable statistics on health or economic outcomes can be extremely detailed, granular and useful for ensuring that policies and programmes target the outcomes that matter for the furthest behind.

But it is limited. Coverage of these data sets can often miss the most marginalised groups; homeless or incarcerated populations for example often do not feature in these survey samples. A lot of this data is several years out of date. It may also fail to ask the most locally-relevant questions with respect to the dimensions of poverty that really matter, identify the sensitive or stigmatising variables, such as ethnicity, or sexuality, that are the basis for people’s exclusion, or relate to the particular policy questions that national actors are grappling with.

Meaningful inclusion of people throughout the data life cycle to shift power imbalances

Beyond focussed targeting, a LNOB approach should also seek to challenge the structural drivers of inequality that exclude people in the first place. Data and evidence can help to shed light on what these drivers are, and what barriers to inclusion people face. Statistical analysis of the data sets described above can start to identify potential causal relationships, complemented by a range of more qualitative analysis, reviewing the political economy for example, can help to understand why there may be measurable inequalities between different groups.

But this can only take you so far. Analysis that recognises the furthest behind as only as passive data points will fail to use the opportunity of the process of data collection, analysis and dissemination to change how people can have a voice and be empowered in their own development.

Nationally owned and inclusive data can address many of the limitations associated with commonly used internationally comparable data sets.

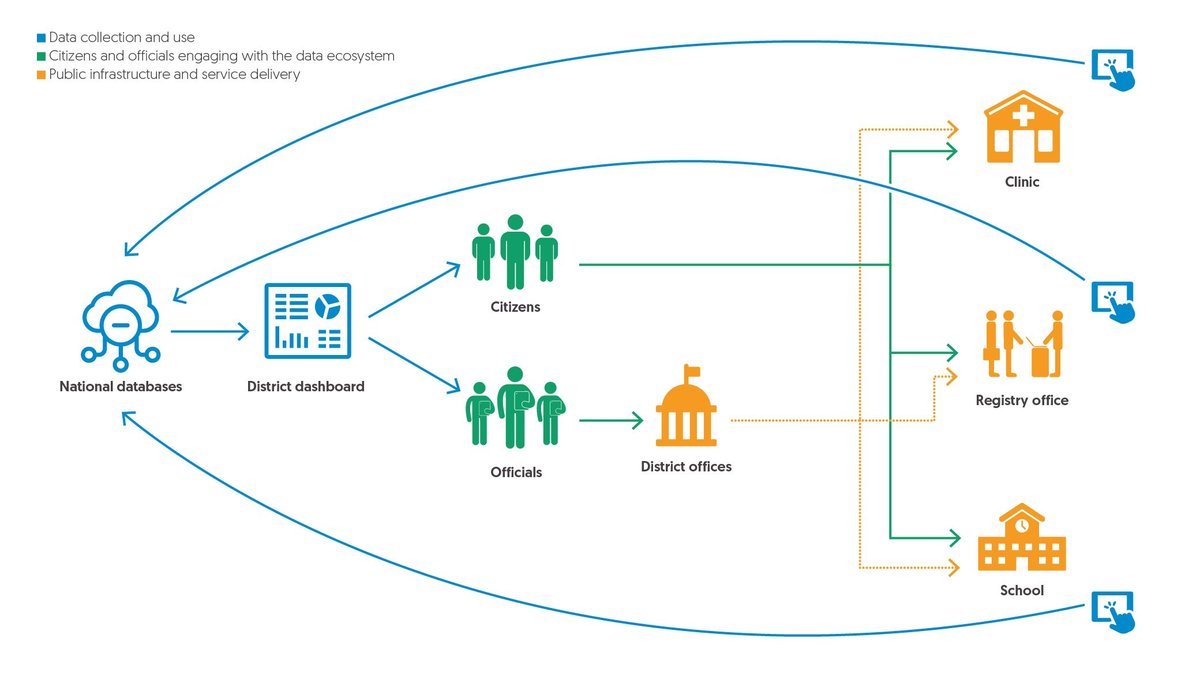

Data landscaping recognises the importance of an integrated and sustainable data ecosystem as foundational to any data analysis

DI’s systematic ‘data landscaping’ reviews not only the indicators that can tell you about people’s outcomes in existing data sets, but also the quality of that data, the infrastructure that sits behind it and its integration with the wider data ecosystem. If data is to be used systematically to leave no one behind, it needs to be consistently robust, timely and relevant, with data use embedded within decision making structures and institutions.

We identified how nationally-owned administrative data in particular has the potential to be the most vital, timely and relevant sources of data that can practicably inform decision making. Thai data is asking relevant questions to inform policies, because it’s collecting data at the point of service delivery, in the language of the departments and ministries that make sense in the national context. But unfortunately, this is yet to fulfil its potential in many countries, in part due to development finance in support of statistics not giving sufficient focus towards strengthening these systems in a coherent way that promotes national ownership. This is a topic of focus in the upcoming Global Partnership 2022 Effective Development Co-operation Summit.

A foundational data ecosystem

Community-generated data can fill in important gaps

The process of collecting, managing, analysing and sharing data can also play a role in challenging the norms and power dynamics that can drive inequalities. By putting people and their interests at the centre of the data lifecycle, rather than simply being subjects of diagnostics, the data process itself can be a powerful tool to leave no one behind.

We have been working with the Leave No One Behind Partnership to support efforts to put data that captures people’s lived experiences, priorities and interests at the heart of decision-making spaces. Seven different country coalitions have identified population groups or issues where the data is inadequate to ensure informed decision making, and have been working to fill these gaps with community generated data (CGD).

CGD is different from official statistics. The resources, data collection systems and infrastructure are not comparable. But that does not make this data invalid, rather, when collected, stored, analysed and shared using a transparent and robust approach, it can provide essential insights that the most rigorous survey would miss. DI are supporting these coalitions to ensure transparency and robustness in the CGD process, so this data can be used effectively to empower marginalised groups, by making their voices heard and count and influence decking making.