Policy Research on China-EU-South Africa Diplomatic and Economic Relations

Simon Tanios, Daniele Barro, Elaha Nayaab, Tapiwa Penama and Noemi Altobelli

Abstract

China-South Africa relations have been developing in multi-faceted partnerships, stemming from historical links, strategic objectives, and mutual interests, and taking place through diplomatic partnerships, security cooperation, economic ties, and community relations. What enhances the particular relation between China and South Africa is the presence of the continent’s largest and oldest Chinese community in South Africa, an agglomeration of Confucian Institutes, and a growing Chinese media influence. On the other hand, with the ongoing mechanisms of international cooperation through the Forum of China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), the G-20, and Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) grouping, South Africa-China ties are taking an important significance in the international and global affairs. However, differences between China and South Africa continue to shape the relations between them and distinguish the latter from China’s relations with other African countries.

In general, China’s rise in Africa grew with China’s increasing Gross Domestic Product (GDP), trade, and overseas investment. This has forced the European Union (EU) to rethink its relationship with both parties. This paper examines, in particular, China-South Africa relations. Following the scheme of the stages in the development of public policy, it provides useful information for policy development undertaken by the EU concerning increasing China’s presence in South Africa. The importance of this paper is that it exposes China-South Africa relations in main strategic sectors, showing sights where the EU can play a role taking into consideration its position and strategies, and South Africa as state and general public reaction towards global players.

Keywords: China, South Africa, European Union, and cooperation.

I. Introduction

The increasing presence and visibility of China in South Africa in the past decade is highly remarkable. The two countries are seen in a honeymoon stage, and questions are raised on how far this relationship can reach in the coming future. On one hand, China is considered today as the world’s second-largest economy after the United States and given its size, central to important regional and global development issues (World Bank, 2020). On the other hand, South Africa is one of the continent’s largest economies, alongside Nigeria (International Monetary Fund, 2019). The evolving relationship between these two countries confronts a larger set of questions on the influence of that growing relationship on regional and global affairs.

Arguably China has jumped at the opportunity to increase its engagement in South Africa, and the latter has widely opened its arms to China. Laribee even described South Africa as the “China” of Africa, as they share many common characteristics (Laribee, 2008). However, while this relationship is intensifying, critics are raised inside and outside South Africa from “Chinese new colonization”, “Propaganda of China’s South-South Solidarity”, to even “China is buying South Africa silence”.

What is the nature of the Chinese engagement in South Africa and what makes it different from other African countries? How the relationship evolved? What are the expectations for the future? And what role can the EU play in this context? This article reflects on these questions while acknowledging that it can only scratch the surface of this large, multi-faceted, and complex relationship. It builds on previous works focusing on Sino-African relations in general, and Sino-South African relations, providing useful insights for policy development in this context at the EU level.

II. Historical Overview

Contemporary relations between China and South Africa rooted back to the late 19th century when a small number of Chinese migrants from Mauritius and the Southern coastal regions of China settled in the British colonies and the Boer Republics (parts of what is now the country of South Africa) as part of an international wave of fortune seekers drawn to the discovery of gold and diamonds. This was supplemented by a formal labor recruitment scheme organized by mining companies which brought thousands of Chinese workers to the country. Sooner, the Chinese community set up a Chinatown in Central Johannesburg (Wu & Alden, 2014).

In the subsequent decades, South Africa’s official relationship with China became a function of British imperial ties with the government of the Republic of China (ROC). In line with London, South African officials established links with the ROC in 1931 during the period in which the South African Communist Party (SACP) was founded, in 1921. At that period, South Africa was closely aligned with the Soviet Union and issued repeated declarations of support for the communist liberation of China (Ibid).

After the election of the National Party in 1948, the Chinese community in South Africa found itself subject to the systemized racial policy towards the “non-whites”. However, formal ties between the two countries continued to be mediated by the British Foreign Office and Washington (Yap & Man, 1996).

The announcement of Nelson Mandela’s release in February 1990 was followed, a year later, by discussions with South African diplomats in Beijing aimed at setting the stage for formalized ties. In January 1998, the two countries established formal diplomatic ties and started a period of gradually intensifying bilateral political engagement, and cooperation on different levels (Chris & Yu shan, 2014).

III. Diplomacy and Strategic Partnership

The initial period of formal diplomatic relations between China and South Africa started when the Pretoria Declaration was signed in 2000 (Ibid). It focuses on the establishment of a bi-national commission with a commitment to improving favorable conditions to mutual economic benefits in the form of expanding trade and investment, especially in the areas of natural resources, mining, and manufacturing (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC, 2000).

After Pretoria Declaration, relations evolved quickly where coordination between China and South Africa were going on different levels, notably during the work of the established bi-national commissions, the launching of China’s Forum on China–Africa Cooperation, in the World Trade Organization, at the G8-Africa summit in 2005, and after the induction of South Africa in Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC) grouping in 2010. The latter seems to establish South Africa as a strategic geopolitical partner of China and a major player on the African continent.

A second phase of diplomatic relations was seen taking place after the 2010 Beijing Declaration when South Africa was upgraded to the diplomatic status of Strategic Comprehensive Partner by the Chinese Government (Ross, 2016). From a political point of view, this strategic partnership between the two countries helps to limit the international space of Taiwan as China sets a pre-condition of non-recognition of Taiwan as a foundation for any future investment and financial aid (Papatheologou, 2014).

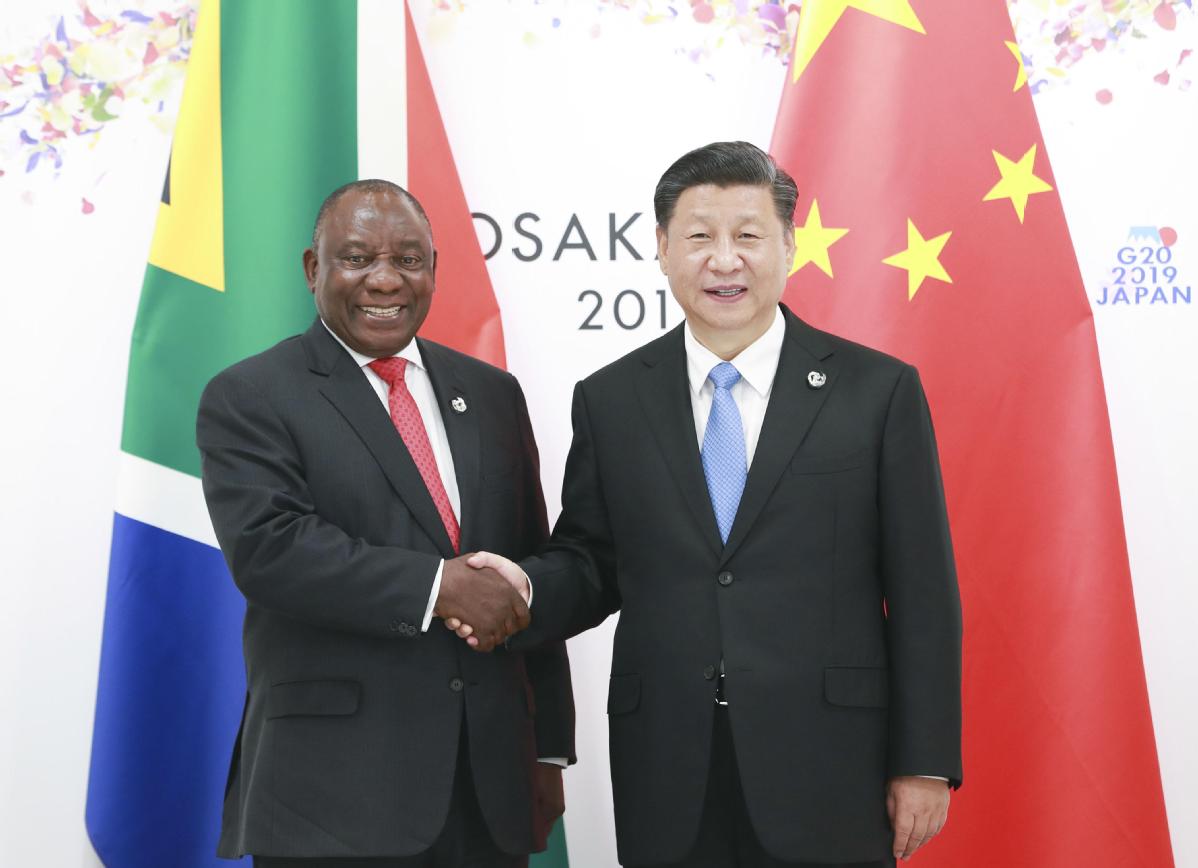

President Xi Jinping shakes hands with his South African counterpart, Cyril Ramaphosa, on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Osaka, Japan, June 28, 2019 ©CHINADAILY.

In 2013, China's Belt and Road initiative was unveiled. Many investment opportunities for Chinese enterprises were opened in areas such as ocean economics, renewable energy, seafood, and marine tourism. In 2015, the two countries signed 26 agreements with a combined value of $16.5 billion during Chinese President Xi Jinping state visit to South Africa (South Africa Government, 2015). In 2019, during the G20 Summit in Japan and BRICS leaders’ meeting, Chinese President Xi Jinping and South Africa President Cyril Ramaphosa renewed their commitment to strengthen the alignment of the Belt and Road Initiative and eight major initiatives agreed at the 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on the China-Africa Cooperation, deepening cooperation in infrastructure construction, digital economy, and high technology (Xinhua, 2019).

IV. Soft Power

Following Nye definition of soft power pillars, namely related to one country’s culture, political values, and foreign policy (Nye, 1990), the “Beijing Consensus” based on the principles of Chinese Taoist tradition emphasizing on non-hegemony, no-interference, and no alliances (Naidu, 2007) puts China’s soft power strategy in an advanced position relative to other global players.

The concentration of Confucius institutes in South Africa constitutes one articulation of China’s soft power strategy. These institutes are joint ventures between Chinese and foreign universities to promote the broad picture of Chinese identity, allowing China to foster its culture within South African’s society, increasing consequently its influence in the country and Africa as a whole.

In addition, the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which was an initiative formally proposed and launched by China, helps the latter to tighten its relationship with African countries in general, and South Africa in particular. Differently from the Western approach to funding development countries, China's use of soft power through the AIIB is evident in its approach to better respect the borrowers’ choice to development and limiting political conditions to the minimum (Huang, et al., 2016). Even though South Africa has not formally joined the bank, but it is foreseen as a prospective Founding Member in the near coming future.

V. Trade

China-South Africa's economic relations have progressed at a rapid pace over a relatively short time. In 2008, only a decade after formal diplomatic links were established, China was one of South Africa's primary import and export trade partners. Since 1998 bilateral trade has been on a steadily upward rise, despite inconsistencies in data produced by both countries, mainly due to technical and political factors, currency fluctuations, and the role of intermediaries such as Hong Kong for instance. This rapid growth in trade is seen as the result of a combination of bilateral friendship and global factors. These include China joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, and with the formal recognition by Pretoria of China’s market economy status, upgrading their economic ties to a strategic partnership in 2004.

Since 2004, South Africa is experiencing a deficit in the balance of trade where the disproportion between exports and imports from China is identified as one of the main contributors to that deficit (imports from China accounted for 10% of South Africa’s total imports in 2010) (Gonzalez-Nuñez, 2010). Data from 2011 shows China as the first import source country for South Africa followed by Germany, United States, and Japan, but it was the fifth in terms of export markets for South Africa where the United States, Germany, Japan, and Zimbabwe were in the top four (South Africa Department of Trade and Industry, 2012). Also, apart from the trade balance, there are concerns about the structure of trade where China imports minimal value-added products from South Africa (mainly mineral products) (South Africa Department of Trade and Industry, 2012) while the latter imports Chinese value-added manufactured products.

In 2005, negotiations were initiated by Beijing to create a FTA with South Africa. Supporters of the FTA argue that this would help South Africa tackle the problem of trade imbalance, improve employment, and draw investment opportunities in the mining sector. On the other hand, this would disadvantage other Southern African Customs Union (SACU) countries whose exports already entered China’s markets. This latter concern was the main contributor to cause the issue to drop off the agenda. However, the FTA has recently returned to the discussions between Pretoria and Beijing.

After the 2008 financial crisis, two-way trade has flourished between China and South Africa (Wu & Alden, 2014). During the first half of 2009, a 32.8% drop in imports was estimated from major import economies, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members and EU states (Wu & Alden, 2014). In this context, China became one of the largest trading partners of both South Africa and the region, and an important factor in South Africa’s resilience to the global economic crisis.

In 2010, China and South Africa signed the Beijing Declaration on the Establishment of a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Between the People's Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa. The latter stated that both countries would work together to ensure more value-added products in South Africa exports to China (South African Government, 2012). In 2013, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to South Africa, both sides signed the Terms of Reference of the Joint Inter-Ministerial Working Group aimed to supplement mechanisms and coordinate the implementation of major projects and bilateral agreements (South Africa Department of International Relations and Cooperation, 2014).

Although China is characterized as a competitor nation, exporting goods to the African region at a lower cost than South Africa can deliver. Interests in expanding commercial ties remain strong. A notable example is the South African Expo in Beijing in 2012 and the active participation of major South African companies in the 17th annual China International Fair for Investment and Trade in Xiamen in 2013 (South Africa Department of International Relations and Cooperation, 2014). China and South Africa are now seen at their honeymoon stage, wherein 2018, South Africa was the second larger exporter to China from Africa, and the first buyer of Chinese goods among African countries (Chinese-Africa Research Initiative, 2018). In 2019, as the outcomes of the Beijing Declaration and 2018 Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Beijing Summit, a Chinese economic and trade delegation signed 93 economic and trade agreements with South Africa, with a direction to increase economic agreements in the future (Embassy of The People's Republic of China in South Africa, 2019).

VI. Investment

Even though expectations of Chinese Investment in South Africa were positively high, until 2007, South African companies have invested more in China than their Chinese counterparts had done in South Africa (Wu & Alden, 2014). Also, figures from 2000 till 2010 show that the actual investment forms a very slight portion of their broad economic relations. For instance, South Africa Reserve Bank data reveals that, except for 2008, China was a modest source of FDI for South Africa from 1997 till 2010 in comparison with other countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and United States (Sandrey, 2013). However, in the last 10 years, the Chinese investment in South Africa increased substantially, reaching 38% of total trade between the two countries in 2017 (Torrens, 2018). Despite this evolution, figures from UNCTAD, as reported by Wu and Alden reveal that China FDI stocks in South Africa were about 5.1 Bn $ compared to the EU’s 124.3 Bn $ in 2012 (Wu & Alden, 2014). However, EU businesses, particularly in the oil and infrastructure sectors, feel the pressure of Chinese competition. At the same time, these same businesses benefit from Chinese investment that can generate more business for their services. Even though the trend of Chinese investment in South Africa is substantially increasing, China has a long way to go to match the EU’s FDI stock figures.

Although South Africa is a resource-rich country, it is viewed as maturing in economic terms. Opportunities for outside investors in South Africa’s markets face many obstacles such as the regulatory environment, rigid labor market, strong position of trade unions, and promotion of black economic empowerment (BEE). The latter requires businesses to provide company assets to black South Africans, creating obstacles to outside investors that take time to overcome. As a response, Chinese investment in South Africa consists primarily of joint ventures and brownfield investments, with the bulk in the mining sector mainly by Chinese State-led corporates (Wu & Alden, 2014). The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) coupled with the opening of the China Africa Development Fund (CADFund) office in Johannesburg plays a role in crowding-in Chinese investment in South Africa. To date, the main investments are in sectors like mining, cement, solar and power projects, transportation networks, banking, and agriculture. Regarding South African’s FDI in China, the overall motivation is internationalization and resource/market seeking but is distinctive in that it was initially led by private corporates, mostly in the mining sector, food and beverage industry, telecommunications, and media (Wu & Alden, 2014).

VII. Security

South Africa and China are seen to have “complementary advantages”. On one hand, South Africa has a very good defense industry thanks to its ties with many world-class research institutes. On the other hand, China is one of the world’s top manufacturers and industrial producers. Therefore, both countries take advantage of joining defense technology research labs and exchanging technologies (Wingrin, 2019).

According to the Pretoria Declaration signed in 2000, the two parties agreed to the establishment of a Chinese–South African defense committee (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC, 2000). The military cooperation includes providing electronic equipment to the South African National Defense Force and training South African soldiers. In parallel, since the signature of the Beijing Declaration in 2000, commercial transactions between South Africa’s armaments and the Chinese military have increased, as well as academic and research exchanges in the field of security. In 2010, the Chinese and South African police have signed an agreement aimed at improving cooperation on international crime. The latter helps to consolidate and exchange intelligence information such as drug trafficking, illegal immigration, money laundering, arms smuggling, and human trafficking (Xinhua, 2010).

VIII. Public Interaction

The experience of many South African manufacturing firms facing Chinese competition has become illustrative of critics in South Africa on unfair economic relations. As an example, an industry in South Africa that employed 230,000 South Africans in 1995, and was the sixth-largest exporter in the world, suffered from direct job losses of about 85,000 due to identified Chinese competition (Wu & Alden, 2014). The continuing job losses in the manufacturing industry due to Chinese imports have made the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) one of its most vocal critics. In 2013, the secretary-general of COSATU bluntly characterized the role of China, calling its policies 'colonial' and in line with the exploitative relations with traditional Western industrialized economies. However, other unionists see more positive long-term impacts emerging from deepening economic engagement with China, especially regarding learning and technology transfer (Ibid).

On the other hand, Chinese media in South Africa have been engaged in a varied range of activities, including content production and distribution, infrastructure development, direct investment in local media, and training of journalists. A study showed that although some South African adopt Chinese media in their daily news consumption, skepticism towards China, and by extension its media, dominates (Madrid-Morales & Wasserman, 2014).

IX. Recommendations

After exposing the nature of China-South Africa multifaceted relation, its evolution over time, and future expectations, the following paragraphs reflect on problems and opportunities that might be associated with this growing relationship. Following the stages of development of a public policy identified by Trudgill (Trudgill, 1990) as cited by Johnston and Plummer in their work to explain the nature of policy-oriented research (Johnston & Plummer, 2005), we try to identify the sources of the problems and opportunities aforementioned, and how the EU can play a role in this context, taking into consideration its resources and position on South Africa, regional and international arenas.

Strong ties and common interests are shared by China and South Africa, and their growing relationship at this stage is a reality to be accepted and dealt with. It is obvious that this new dynamic undermines the EU’s position in key economic and normative areas and weakened Western monopoly as preferred financiers (Kopinski & Sun, 2016). Coupled to this, from the European viewpoints, and regarding Africa as a whole, the Chinese no-interference policy has its implications on EU conditional aid to the promotion of human rights, democracy, and rule of law (Papatheologou, 2014).

On the other hand, while the EU holds by far the biggest FDI stock in South Africa, Chinese investments stimulate the business environment that likely expands EU companies' services in the country. In addition, Chinese investments support the development of many sectors and push towards industrialization, which in return can enhance external business cooperation between the EU and South Africa if coupled with proper policies.

South Africa has hybrid regime where people enjoy a certain level of democracy. This differs from many other African countries and offers an opportunity for more cooperation between the EU and South Africa. On the other side, with the increasing competition of global powers, any absence of cooperation might lead to regional economic and political instability, taking into consideration the important role of South Africa in the continent. This cooperation should support the business environment and promote equal partnership based on trust and dialogue.

China’s engagement in South Africa can provide great opportunities for trilateral cooperation to the EU. This framework is driven by shared interest, designed to bring together the high production capacity of China, the advanced technologies of developed states, and the need of developing nations (Duchâtel, 2019). Trilateral business ventures offer a space to apply the aforementioned model. In this context, South Africa's management responsibility would contribute to the establishment of a level playing field, thus contributing to integrating South Africa viewpoints and priorities. In other terms, the EU should seek exchange with South African authorities changing the perception of South Africans on the current political arena of the EU imposing its westernized standards as a condition for positive engagement in the country.

Identification of the sectors in which the EU will engage should be in close coordination with South African authorities, and even regional bodies, thus stimulating regional integration, promoting dialogue, and achieving strategic interests where all parties involved can benefit. The EU can use its existing funding instruments for that purpose, and backing up European companies, thus reducing the risk of private investors. A priori we can identify two strategic sectors where co-funding by China and the EU, with the management responsibility by South Africa, can bring benefits to all. The first sector is in renewable energy. The South African energy crisis began in 2007, and according to Eskom (a South African electricity public utility), controlled rationing of the power supply is applied across the country (Business Insider South Africa, 2019). A more effective energy supply coupled with knowledge transfer is an opportunity for the trilateral cooperation to take place, which in return can stimulate the business environment. Another sector of cooperation is ICT (Information, Communication, and Technology). Advancement in this sector is a strategic interest for South Africa to grow faster the economy and boost the GDP. In return, this sector can have high returns to external investors as the EU for instance.

In addition, the EU can promote its comparative advantages concerning human rights and good governance, regarding international working standards in the South African work environment. Sharing knowledge and increasing investment to promote a green transition, digital transformation, education, research, and innovation are also key sectors where the EU can play a role.

X. Conclusion

This essay highlights how the relations between South Africa and China have evolved over time, and how the EU can play a major role in bilateral and trilateral cooperation that can benefit parties involved. Cooperation with South Africa should continue through the promotion of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, and the support of the right of people to determine their own destiny. There is also a space for trilateral cooperation in business ventures involving China where each party can use its comparative advantages in strategic sectors that have high returns to all.

References

Business Insider South Africa, 2019. Eskom is now rationing electricity at stage 6. https://www.businessinsider.co.za/what-is-stage-6-load-shedding-eskom-l…(Accessed 5 May 2020).

Duchâtel, M., 2019. Triple Win? China and Third-Market Cooperation. https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/triple-win-china-and-third-ma…(Accessed 5 May 2020).

Huang, M., Chen, N. & Chen, Y., 2016. An analysis on the potential competitiveness of the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank. Asian Infrastructure Development Bank.

International Monetary Fund, 2019. Sub-Saharan Africa: recovery amid elevated uncertainty. The Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa, p. IX.

Johnston, R. & Plummer, P., 2005. What is policy-oriented research?. Environment and Planning A, Volume 37, pp. 1521-1526.

Kopinski, D. & Sun, Q., 2016. New Friends, Old Friends? The World Bank and Africa when the Chinese are Coming. Global Governance, Volume 20, pp. 601-623.

Laribee, R., 2008. The China Shop Phenomenon: Trade Supply within the Chinese Diaspora in South Africa. Africa Spectrum, Volume 43, pp. 353-370.

Madrid-Morales, D. & Wasserman, H., 2014. Chinese Media Engagement in South Africa. Journalism Studies.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC, 2000. Pretoria Declaration. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ce/ceza/eng/zghfz/zngx/t165286.htm(Accessed 7 May 2020).

Naidu, S., 2007. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation(FOCAC) What does the future hold?. China Report Sage, Volume 43:283.

Nye, J., 1990. Soft Power. Slate Group, LLC.

Papatheologou, V., 2014. EU, China, Africa towards a trilateral cooperation: Prospects and Challenges for Africa's Development. Journal of African Studies and Development, Volume 6(5), pp. 78-86.

Ross, A., 2016. South Africa and China: Behind the smoke and mirrors. Main and Guardian, http://mg.co.za/article/2016-01-11-south-africa-and-china-behind-the-sm…(Accessed 5 May 2020).

South Africa Government, 2015. Government signs 26 agreements worth R94 billion with China. https://www.gov.za/speeches/government-signs-twenty-six-agreements-wort…(Accessed 2 May 2020).

Trudgill, S., 1990. Barriers to a Better Environment: What Stops Us Solving Environmental.

Wingrin, D., 2019. China looks to increase defense ties with South Africa. DefenceWeb, https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/china-looks-to-increase-defence-t…(Accessed 3 May 2020).

World Bank, 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview(Accessed 3 May 2020).

Wu, Y.-S. & Alden, C., 2014. South Africa and China: The Making of a Partnership. The South African Institute of International Affairs.

Wu, Y.-S. & Alden, C., 2014. South Africa and China: The Making of a Partnership. The South African Institute of International Affairs.

Xinhua, 2010. South Africa and China sign police agreement. China.org, http://www.china.org.cn/world/2010-08/01/content_20616263.htm(Accessed 5 May 2020).

Yap, M. & Man, D. L., 1996. Living in between: The Chinese in South Africa. Migration Policy Institute.